The embattled Doe Run lead smelting facility in Peru may finally be getting a break. We met with Dr. Juan Carlos Huyhua, the president of Doe Run Peru, in New York last week to get an update on the situation.

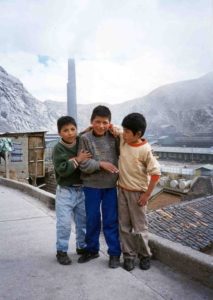

Three years ago, the plant was shut down by a mixture of politics and litigation. So work installing new pollution mitigating technologies at the plant stopped, cleanup was halted, and the people of La Oroya were left without work and a legacy of pollution. But not without income – we learned that the refinery has continued to pay salaries for 4,000 employees, even while the plant has been closed. That good citizenship may now be paying off.

We’ve been told that the government of Peru is working to reach a consensus to approve a plan for Doe Run Peru within 60 days, by April 12. If everything goes well, the company expects the plant will reopen, appropriately, on May 1- labor day.

“It is a very positive message for the country that finally, working together – the state, the company and community – it is possible to solve an issue that is dated more than 90 years,” Dr. Huyhua told me.

After three years of no movement, he interprets the government’s actions as a “vote of trust” for his company. And he is ready to go forward. Dr. Huyhua told us that Doe Run Peru plans to invest up to $200 million more in environmental projects within 30 months. The company has also continued to support the public health programs in La Oroya during the plant’s closure.

“We believe in the business,” he told me. “We consider that an investment because La Oroya needs technical people and we need to keep them.” He reiterated that it all depends now on the government. “Everyone has to work together to get results and what’s better for the country. And that’s to reopen the plant.”

And we do agree. While corporations like Doe Run Peru are often vilified, and many are guilty of unspeakable pollution, they can be moved to make a difference because they have the resources to do so and the incentive.

This is the only way forward for the people of La Oroya, because the alternative is a stalemate in which nothing happens. No one wins if the smelter is left shut down and contaminated. But finally installing state- of-the-art pollution management technology, and restoring livelihoods for thousands in the Andes is a goal worth reaching for. And only then can the cleanup of legacy contamination around the town begin as well.

With the company and the government of Peru now on the same path, all this might happen. It is the only practical solution to a massive problem.

Related: Surprise – Corporations NOT the worst pollution problems

I was most encouraged by your article and I agree wholeheartedly with the sentiments you express. Having had some involvement in the industry in dealing with the issues of smelter emissions and the effects of smelter pollution I can vouch for the effectiveness of the collaborative approach. It works; and ultimately everyone wins, most importantly the local residents who are directly affected. That must be the focus: not who is to blame and who is responsible for what, but how can we collectively and cooperatively work together to fix the problem. ‘We’ must include the local community as an equal partner if the process is to be successful; trust and respect must be earned.

Graham Kenyon

Trail BC

Canada