Hot and toxic piles of rice husk ash pollute and threaten rice-producing communities in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is the world’s third-largest rice producer, with 36 million metric tons of rice produced in 2020 alone. This bounty has come at a cost to some local communities in the form of rice husk pollution. This was one of the pollution problems identified earlier this year by local residents at a workshop organized by Pure Earth Bangladesh and local partner The Hunger Project, in the district of Naogaon, where over 1200 rice and husking mills are located.

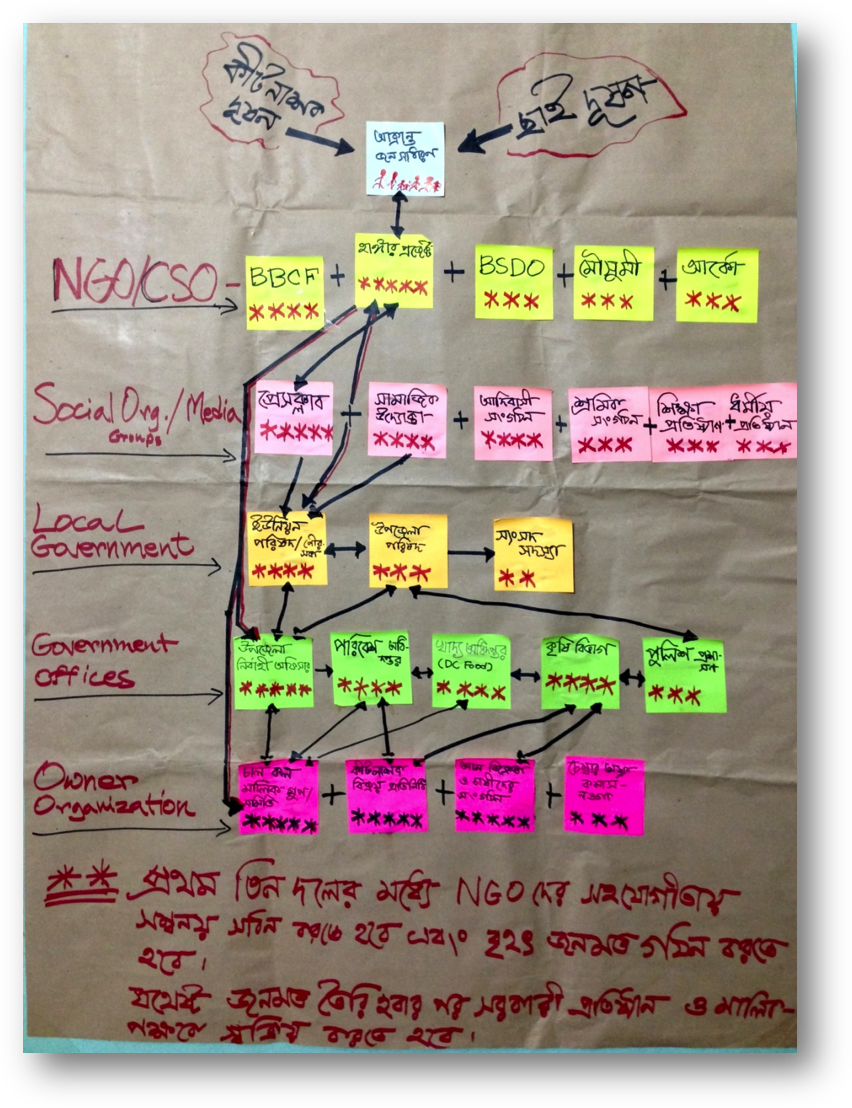

The day-long event, “Workshop on Environmental Pollution and its Remedies,” attracted 24 participants, and was followed by an online discussion a few weeks later with 96 participants, including rice mill owners, rice mill laborers, local environmental activists, government officials, leaders of local indigenous communities, journalists, school teachers, school and college students, public health experts, and other community leaders.

The workshop and online discussion gave participants the opportunity to voice their concerns, share stories about how pollution is affecting them, and empower them to work with each other to find solutions.

What is Rice Husk Pollution?

One of the by-products generated by rice mills is rice husk. The husk, which covers the paddy grain, accounts for 22% of the weight of a paddy. This husk is used as fuel in the rice mills to generate steam for the parboiling process. This generates ash out of the husk, known as rice husk ash (RHA). Rice mills in Bangladesh generated more than 2.5 metric tons of RHA in 2020.

Most mills are located by main roads and highways, so that paddy can be brought to the mill, and parboiled rice can be easily transported all over the country easily. As a result, hot and toxic RHA is often dumped by highways and in other public places like farm lands and open spaces near residential areas. It is common to see piles (sometimes hills) of hot ash near most rice mills. Passing vehicles send the RHA flying around, filling the air with microscopic particles that can get into eyes and respiratory systems of passersby.

At the workshop, a school teacher shared a tragic story of a little girl, the daughter of a neighbor, who died after falling into a pile of hot husk ash while playing. Another teacher told the story of an elderly neighbor who burned her leg on a pile of hot ash.

More than one participant talked about people they knew who lost their eyesight, like forty-five year old Momena Begum (left), who lost her right eye three years ago when hot ash flew into her eye as she was returning from work.

More than one participant talked about people they knew who lost their eyesight, like forty-five year old Momena Begum (left), who lost her right eye three years ago when hot ash flew into her eye as she was returning from work.

Participants complained of polluted smoke and ash spreading through villages, covering their clean laundry, contaminating the soil and water.

Taking Action

Through discussions at these collaborative meetings, the community identified their preferred solution – recycling the rice husk into charcoal, which would not only help address the problem, but also provide employment opportunities to local youths and unemployed community people, especially women.

Pure Earth and The Hunger Project will provide support through a sustainable partnership with a master craftsperson from a local charcoal manufacturing mill to provide skills training on recycling the rice husk.

Besides rice husk pollution, locals also expressed concern about pesticide use in nearby mango plantations. Another pollution problem–the use of pesticides in tea estates–was identified at an earlier workshop in Kulaora, another district of Bangladesh that is home to the most tea plantations in the country.

The overall goal of these community outreach initiatives is to empower local residents to identify pollution problems impacting their lives, and to take action. The workshops in Bangladesh are part of Pure Earth’s pilot global community outreach initiative, which works with local civil society organizations (CSOs) to identify and address environmental justice issues among women, youth, and other under-represented populations. In addition to Bangladesh, Pure Earth has also activated communities in Colombia and Senegal, with more to follow.

Learn more:

https://www.pureearth.org/blog/activating-communities-to-solve-pollution/

https://www.pureearth.org/blog/bangladesh-mobilizing-tea-worker-communities-for-pesticide-safety/