Pure Earth/CINCIA rainforest reforestation team in Peru.

Pure Earth/CINCIA rainforest reforestation team in Peru.

In South America, alluvial gold mining is degrading the Amazon basin at an unprecedented rate, leaving barren craters in previously lush rainforest. Pure Earth is working on a rainforest reforestation project to restore the area.

The worst damage is happening in the Peruvian region of Madre de Dios, one of the most biodiverse and pristine areas in the world. The soaring global demand for gold in the last decade has attracted thousands of poor migrants looking for gold and a better future.

The damage from gold mining is clearly visible in the rainforest. Previously lush greenery is now scattered with barren craters.

The damage from gold mining is clearly visible in the rainforest. Previously lush greenery is now scattered with barren craters.

While the situation is dire, there is a way to protect the endangered forest without stripping the miners of their livelihood.

Since December 2017, Pure Earth has collaborated with CINCIA (Amazon Center of Scientific Innovation) to ecologically restore areas degraded by mining and help miners responsibly close their mining concessions once they are ready to move on to mine in a new area.

Rainforest reforestation – transporting seedlings

Rainforest reforestation – transporting seedlings

The first site Pure Earth and CINCIA worked to restore was the Paolita II mining concession in Madre de Dios.

The team planted 4,166 seedlings in December 2017, and returned a few months later in March 2018 to introduce an additional 744 seedlings to reinforce initial growth at the former mining site.

Pure Earth project leader France Cabanillas recently revisited the Paolita II site and reported that regrowth is on track.

Rainforest reforestation – A signboard explains the replanting at the Paolita II site, a project by Pure Earth and CINCIA

Rainforest reforestation – A signboard explains the replanting at the Paolita II site, a project by Pure Earth and CINCIA

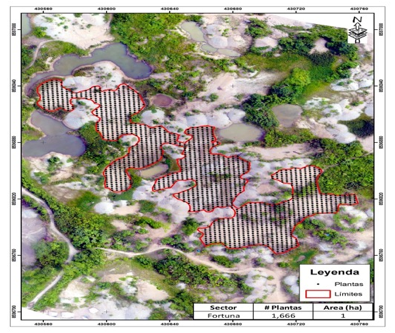

Then in November 2018, Pure Earth reunited with CINCIA and mining leaders to work on restoring a new site–one hectare of degraded rainforest in the adjacent Fortuna Milagritos mining concession.

Together, Pure Earth and CINCIA have started the rehabilitation of about 3.5 hectares of rainforest at the two sites.

While the two replanted areas represent just a fraction of the deforestation (between 1999 and 2016, gold mining resulted in the removal of 68,228 hectares of rainforest in Madre de Dios), they are now models of hope, demonstrating that degraded mining areas can be brought back to life.

Rainforest reforestation – A Pure Earth/CINCIA A team member planting a seedling in the degraded Fortuna Milagritos site in November 2018.

Rainforest reforestation – A Pure Earth/CINCIA A team member planting a seedling in the degraded Fortuna Milagritos site in November 2018.

The key, according to Cabanillas, is collaboration: “We have learned that we have to work with the miners directly to be able to move forward on this issue and unfortunately not many institutions do that.”

Cabanillas has been working in the area since 2011 to find solutions to the damage inflicted by alluvial gold mining and to share this information with the state, private sector and, above all, the miners.

How To Restore A Rainforest

Rainforest reforestation is a process that requires rigorous planning, cutting-edge technology and staggering precision.

Step 1 – Mapping:

The first step is to fly a Phantom 4 drone over the site to create an “orthomosaic” map, used to identify the areas most in need of restoration.

Without the drone, this task would have been less accurate and considerably more time-consuming.

Step 2 – Plant/Species Selection:

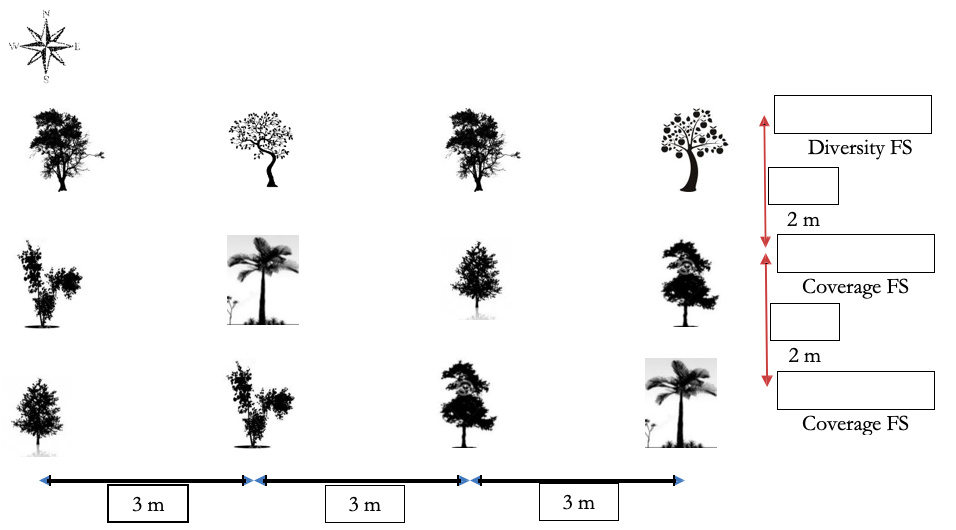

While nine plant species were selected for the Paolita II site, twelve plant species were chosen for the Fortuna Milagritos site based on CINCIA’s longstanding research with experimental plots.

Achieving the most sustainable and effective planting strategy is a delicate balance. Fast-growing “pioneer” plants must complement slow-growth species. Also, it’s important that the trees utilize different resources so as not to compete with one another.

Along with developing an ecologically healthy forest, species were selected for future sustainable use.

For instance, the gigantic kapok tree, which can grow up to 60 m in height and 3 m in diameter, provides nesting for the harpy eagle and other fauna, but is also used in the production of plywood and artisanal canoes.

Step 3 – Transportation:

The heavy lifting for this project was done by local residents of the area, including ecology students from the National Amazonian University of Madre de Dios and the National University of San Antonio Abad de Cusco in Puerto Maldonado.

First, the team drove the 1,700 seedlings from Puerto Maldonado to a nearby port, where they were ferried up the Madre de Dios River, and then carried directly to the Fortuna Milagritos site.

The team performed some makeshift adjustments to protect the precious seedlings, like erecting a tarp over the truck-bed to prevent defoliation during the journey.

Even more onerous than carrying the seedlings was hauling 1,700 kilos (about 3,740 pounds) of “biochar” to the site.

Made from recycled chestnut shells, biochar aids the soil’s retention of water and nutrients while preventing the plant from absorbing mercury in the soil. It is an increasingly popular soil amendment and even has potential to mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration.

Step 4 – Planting:

Once all materials were delivered, the team meticulously planted the seedlings at 3 x 2 meter distances in alternating lines between coverage (fast-growing) and diversity (slow-growing) species.

To bolster growth, each seedling was generously planted with a base of hydrogel, 1 kilo of biochar (enriched with molasses and productive microorganisms) and a ring of fertilizer.

Step 5 – Documentation:

The final step in this rich and complex process is record keeping.

Team members measured the height and diameter of all 1,700 planted seedlings in order to monitor future growth. This data will help CINCIA and other rainforest champions improve future reforestations.

Reforestation is all about looking ahead.

While the ecosystem should be self-sufficient in about 30 years, species like the giant kapok tree will continue growing for hundreds of years. This may seem like a long way off, but this forward-thinking perspective is exactly what’s needed for goldmining and the rainforest to coexist.

This post is from Charles Espinosa, Latin America Program Associate. Charlie holds a master’s degree in Latin American Studies from Columbia University.

##

This project was funded by the U.S. Department of State to assist the Peruvian government and civil society in assessing artisanal gold mining sites, planning remediation efforts and strategies for alternative livelihoods, and sustainably restoring affected natural resources. Partners included the Ministry of Environment (MINAM: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente) of Peru.

This project was funded by the U.S. Department of State to assist the Peruvian government and civil society in assessing artisanal gold mining sites, planning remediation efforts and strategies for alternative livelihoods, and sustainably restoring affected natural resources. Partners included the Ministry of Environment (MINAM: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente) of Peru.

Pure Earth also works in many other artisanal gold mining areas around the world to reduce the impact of toxic mercury while maintaining livelihoods. Because different methods work at different sites, project teams test a variety of approaches; some that eliminate the use of mercury entirely, and others that use (and recapture) mercury.

Related: